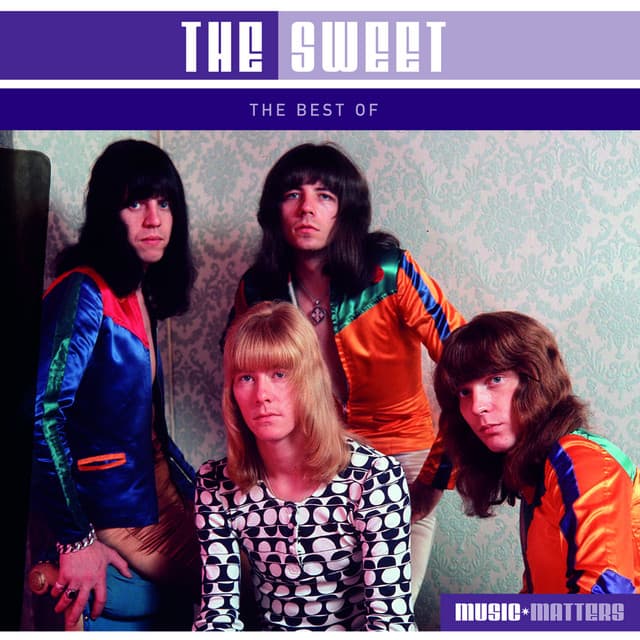

They danced on TV in towering boots and glitter. The record climbed the charts and the crowds sang along. Behind the glitter, Sweet were furious.

In the early 1970s, the British glam rock band Sweet became the public face of a sound they secretly despised. Their standalone single “Poppa Joe” glittered like candy: a sing-along refrain, a jaunty melody and a bright, family-friendly lyric. It also became the clearest proof of a deeper fight — a struggle between the band’s hunger for hard rock authenticity and the commercial machine that shaped them.

Sweet’s members wanted to play loud, raw music. They admired gritty guitar work and songs that carried the weight of their own voices. Instead, they were pushed into a formula by hitmakers Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman, who wrote and produced the band’s most successful singles. The result was pop perfection — and personal torment.

The band’s public image was spectacle: makeup, choreography, and radio-friendly hooks. “Poppa Joe” epitomized that image. It was irresistible to listeners. It soared across Europe and topped the charts in the UK, giving the band success they did not want to be defined by.

“We felt boxed in by the pop machine. The hits paid the bills, but they left our guitars and our songs out in the cold,” said Steve Priest, bassist of Sweet.

That bitterness runs through the song’s story. Band members, especially bassist Steve Priest and lead singer Brian Connolly, longed to break away from the soap-sweet singles. They wanted songs that reflected their musical roots — tougher riffs, grittier lyrics, music that matched how they felt on stage. Instead, they were handed sparkling singles that made them household names but robbed them of control.

Irony sharpened the wound: Brian Connolly’s vocal on “Poppa Joe” is flawless, warm and inviting. He gives the song a joy that the band did not share. That performance made the record a hit and made the band appear to embrace what, in private, they rejected.

“I remember listening to the final master and feeling proud of his voice, but hollow inside. The world heard joy. We heard a cage,” said music journalist and historian Alan Turner, who has followed glam rock for decades.

The conflict between commercial success and artistic identity is not an abstract argument. It had real consequences. Sweet’s repeated releases of upbeat singles kept them on the charts but slowed their move toward harder rock. Their fan base grew, but not always the kind of fans who would follow them into heavier, more serious work. Members felt trapped by the expectations built around their public persona.

There were moments of defiance. The band tried to push original material and edgier arrangements, but producers and record labels, chasing sales, steered them back toward what sold: catchy choruses and safe themes. Behind the scenes, recording sessions were battlegrounds. Producers held the pen and the mixing desk; the band had to fit the parts and perform with enthusiasm they did not feel.

The story of “Poppa Joe” lives on as one of popular music’s sharper contrasts — a deceptively innocent anthem that masks a fierce creative struggle. For listeners who remember the era, the song still evokes sunlit car rides and easy singalongs. For those inside the band, it remained a reminder of compromise — a hit that paid the bills and hollowed out the art.

Yet every time a room full of people sings the “doodle-oo-doo” refrain, that tension crackles: the bright tune in the air and the darker truth humming beneath it — the clash between what the band wanted to be and what the hitmakers insisted they became.