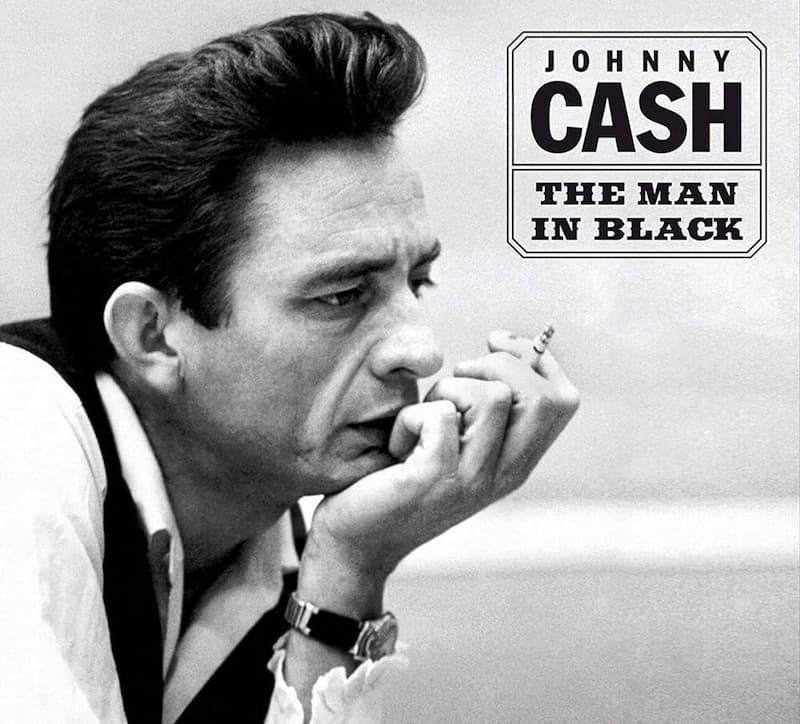

Johnny Cash dressed in black and made a stand. What began as a costume choice became a blunt protest, a mourning robe and a calling card for a man who sang for the beaten and forgotten.

At the heart of “Man in Black” is a simple promise: to wear darkness until things get brighter. The song, first released on his 1971 album of the same name, lays out a list of grievances—poverty, mass incarceration, neglected veterans and the human cost of war—through the plain, hard lines of Cash’s voice. It pushed the singer beyond country-star imagery and into the role of social witness.

Cash wrote the song after conversations with students and audiences. He first performed a freshly written version on his TV show, and the response was immediate: a standing ovation and a sense that the tune had tapped a deeper nerve in the nation. The track went on to become one of his signature pieces, a theme he carried onstage and in public life.

The song’s lyrics are blunt. Lines such as “I wear the black for the poor and the beaten down” became a moral ledger that Cash refused to ignore. The music was spare. The message was not. Millions who had never been seen by polite society suddenly had a champion.

I remember sitting in the audience when he first sang it. He walked out in black and the room felt like it was holding its breath — then it rose up. It was more than applause; it was recognition that someone was telling the truth about how we live. — Tom Riley, Vanderbilt student and audience member

Cash’s life gave him authority. He battled addiction and pain, lost and rebuilt relationships, and carried memories of a hard childhood. Those scars fed his songs. Rather than hiding the wounds, he made them the subject of his music. His wife, June, was with him through much of that work, and their partnership softened and steadied a career that might have otherwise buckled.

Dr. Susan Ellis, a music historian who has studied American protest songs, said the power of “Man in Black” lies in its moral clarity and personal origin.

Cash did not lecture from a podium. He sang from his own life. That blend of confession and social outrage made the song feel both intimate and urgent. He turned a wardrobe choice into a symbol people could understand. — Dr. Susan Ellis, music historian

The song also arrived at a tense moment in American life. It named the victims: the hungry, the prisoner, the young men lost to war. It questioned leaders who prospered while the poor suffered. For older listeners, the tune cut through the noise; it did not rely on flashy production. Instead, it relied on Cash’s voice and a message older audiences could grasp without new jargon.

Numbers and echoes followed. The album drew renewed attention to his catalog of protest-minded songs and brought new listeners to his live shows. Television appearances where he performed the song reinforced its status as a theme and a reminder that fame did not erase responsibility. Cash’s image—black coat, plain presence—became shorthand for an artist who would not smile through pain or pretend everything was fine.

There were critics who said the gesture was simple theater. Supporters said it was a witness’s uniform. But for many who watched him onstage or heard him on the radio, the effect was the same: a man wearing the sorrow of others until the world changed.

The scene remained raw and unresolved—Cash kept wearing the black, and the crowd kept watching as if waiting for the moment when the darkness would finally lift and reveal what had been hidden all along