Jerry Reed stood on the set of a road movie with his guitar slung over his shoulder, and a three‑minute tune changed his life — and the way America heard the open road. “East Bound and Down” did not merely score a chase scene; it became the engine for a cultural moment that still hums on the highway radio.

The song arrived as part of a film about outlaw drivers, CB lingo and beer runs. Reed’s voice — equal parts grit and grin — wrapped itself around a banjo lick and a roar of tires. The result sounded like freedom: fast, a little dangerous, and impossible to forget. For many older listeners, the tune evokes photos of wide shoulders, big rigs and a country soundtrack for working lives.

Reed drew on a hard, honest past. Raised in Georgia cotton fields, he had worked his way up to Nashville with the callouses to prove it. On set, he was laughing with the film’s stars, but the song he wrote came from memory: truckers’ stories, long nights on the interstate, the mixing of rebellion and routine that comes with a life on the road. That plain, tactile truth is what turned a movie cue into an anthem.

The song’s power is simple and practical. Structurally compact and brimming with energy, it was built to be played loud in the cab of a truck. Its language celebrated speed and solidarity — the sense of people who do hard work together and sometimes run up against the law for the thrill of it. That feeling tapped into a late‑century American mood when CB radios and outlaw country were fixtures of everyday life.

Musicians and historians say the tune bridged country tradition and a modern, kinetic sound.

“Jerry didn’t write from a room in a tower. He wrote from the seat of a rig,” said Mark Ellis, a music historian who studies country and American roots music. “You can hear the road in every measure.”

On set, the image matched the music. Burt Reynolds and Reed exchanged laughs while cameras rolled, but the song carried its own story: the pride of work, the joy of speed, the camaraderie of people who share the same miles. For older fans, the song is a time machine, a short ride back to a simpler, louder world.

It also had a ripple effect. Radio stations that served rural routes and highways put the song into heavy rotation. It became a staple at parties and on jukeboxes. Younger listeners who did not live that life still found the tune irresistible because it converted the ordinary into the epic — a hay field into a horizon, a truck into a troubadour’s stage.

“It turns everyday work into something heroic,” said Susan Palmer, a long‑time radio programmer who curated classic country shows for decades. “People who spent their lives behind the wheel heard themselves in that song.”

Beyond nostalgia, the song helped define an aesthetic. Its sonic mix — twang, drive, and a wink in Reed’s delivery — influenced performers who wanted to make music that felt both lived‑in and larger than life. The film’s success put the tune in front of millions, making it an audio shorthand for speed and escape. For ageing audiences who remember when highways were new and radios were simple, the song is not a record but a companion — the soundtrack to afternoons on the road, to long mixers of work and play.

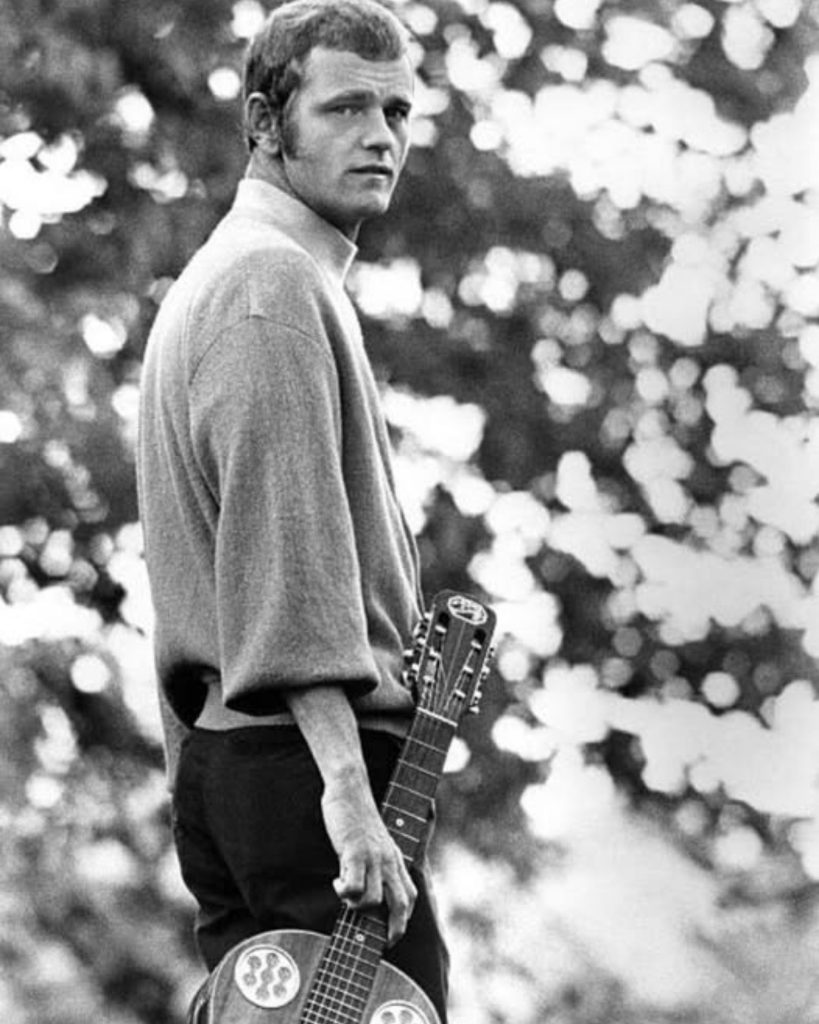

The scene that produced the song is worth picturing: a lean Georgian with a guitar, the hum of a crew, the clap of a director, and a melody born from the smell of asphalt and diesel. That rawness is what let Reed turn a handful of chords into a myth. The result is a three‑minute blast that still makes listeners want to roll down the windows and press the gas — and it leaves the story open, moving toward the horizon