Steely Dan’s “Don’t Take Me Alive” reads like a short, violent film in song — a final vow from a man pushed to the edge, played against a soundtrack of tension and dread. It is not a radio single for the ages. It is a bleak, cinematic monologue that keeps drawing listeners back.

The band retreated from the stage and lived in the studio, polishing songs into razor-sharp narratives. In that era they made records that felt like collections of short stories. “Don’t Take Me Alive” is one of the darkest. The narrator sounds cornered, beaten by life, and ready to die with defiance as his last act. This is not subtle comfort music. It is urgent, raw, and coldly theatrical.

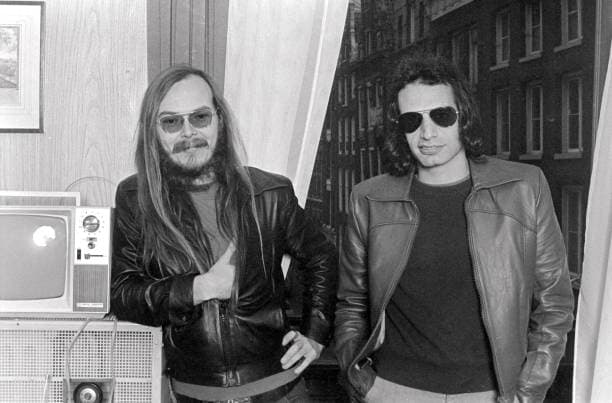

Musically, the song opens with a guitar hook that pricks the skin. The arrangement never lets the tension go. Tight drums, a restless bass line and keyed accents build a sense of a standoff. Donald Fagen’s voice — controlled, a little weary, heavy with irony — becomes the only human thing in a scene of mechanical danger. Walter Becker’s guitar breaks through like a shout: not a technical show-off, but a howl that matches the narrator’s panic.

For many older listeners, the song works as a time capsule. It brings back nights spent listening to album sides and folding in the story as if it were real. People remember hearing it in the dark and feeling every syllable. Its drama comes from the detail and the refusal to soften the edges.

“When I first heard it I felt like I was watching a man make his last stand. The music and the words fit together so tightly, it’s like a short black play.” — Evelyn Carter, longtime Steely Dan fan

The lyrics never tell the whole backstory. They hint. Is the narrator a robber, a fugitive, or a ruined man who lashed out once too often? The ambiguity is the point. The story becomes universal: a person who has lost everything and chooses pride over surrender. The result is a dark moral portrait that can feel painfully close to home for listeners who remember hard times and bad choices.

“It’s a study in desperation and dignity. As a music historian, I find the arrangement ruthless in service of the story. It doesn’t flirt with redemption — it stares at the end.” — Dr. Robert Lang, music historian

Despite its bleakness, or perhaps because of it, the song connected. The album that holds it reached the upper reaches of the charts and delivered songs that had a sharper edge than most mainstream pop. Fans never needed a single to make this track matter. It became a favorite on record players, in late-night listening rooms, and among those who preferred songs that made them think and wince at the same time.

On the surface it is a narrative about a man cornered by police or fate. Underneath, it is a portrait of a culture where pride and stubbornness can turn fatal. The music’s tightness — the clipped phrasing, the sudden guitar bursts, the way the keys cut through — gives each line of the story its own small stage. The guitar solo is a punctuation: jagged, personal, and nearly speechless. It says what words cannot.

For listeners now in their later years, the song carries memory and hardness. It is not a comfort. It is a companion of the sort that sits with you through the night and refuses to let you look away. It stands as proof that rock could still tell a bleak, honest fable, and that an album track could wound as deeply as a hit single —