Johnny Cash turned a movie matinee and a borrowed blues tune into one of country music’s most haunting anthems — then watched it explode into a cultural touchstone and a costly legal fight.

Cash’s rough-edged voice, the spare guitar of the Tennessee Two and a sudden burst of inspiration turned “Folsom Prison Blues” from a roadside idea into a record that changed his career. The song’s power is simple and direct: a man cut off from sunlight, staring at a passing train and the life it carries away.

The origin story reads like a grit-and-glory movie. A young Cash, fresh from service in the Air Force and scraping by in Memphis, formed a band with guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant. After an unpromising first audition, Cash went back to work on new songs. On a quiet afternoon he caught a screening of a prison drama, and the next time he picked up a pen, lines began to form around the picture of a prisoner and a lonesome whistle.

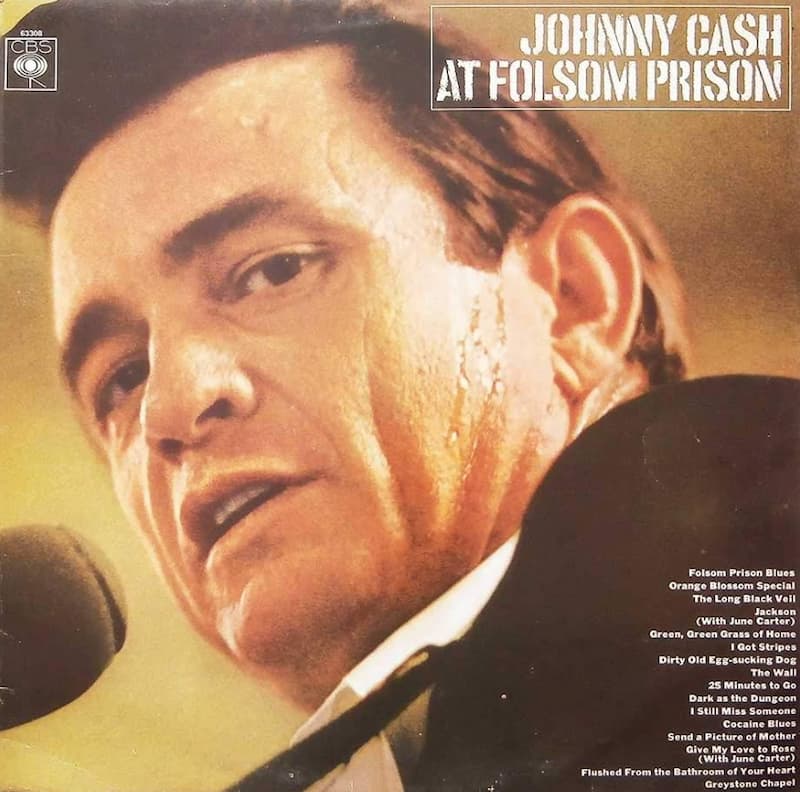

Musically, Cash borrowed heavily from a stormy torch number called “Crescent City Blues,” written by arranger Gordon Jenkins and recorded on a nearly forgotten album. Cash sped up the tempo, added hot guitar licks and recast the lyric into a country narrative centered on Folsom Prison. The first release climbed the country charts and later re-emerged as a live tour de force when Cash recorded a concert inside the prison itself, propelling the song to a larger national audience and into pop territory.

Few songs carry the lived-in sadness of those lines. The lyrics themselves have become part of the record’s testimony.

I hear the train a comin’

It’s rolling round the bend

And I ain’t seen the sunshine since I don’t know when

I’m stuck in Folsom prison, and time keeps draggin’ on

But that train keeps a rollin’ on down to San Antone

— Johnny Cash, singer-songwriter (lyrics)

The success brought attention — and a claim. Gordon Jenkins, the writer of the original “Crescent City Blues,” noticed the close similarity only after the live Folsom recording reached a broad audience. Jenkins filed a plagiarism suit that was settled out of court for a sum reported as $75,000. The settlement left Johnny Cash’s estate in control of the songwriting credit, while acknowledging the financial claim that shadowed the song.

The fight exposed the messy place where influence meets copyright. Music historian and long-time Cash chronicler often point out that Cash acknowledged the source when he spoke about the song, but the legal system moved only after the tune became a mainstream sensation.

When I hear that whistle blowing, I hang my head and cry

— Johnny Cash, singer-songwriter (lyrics)

Numbers and moments matter in this tale. A mid-1950s Sun Records single nudged Cash into the country spotlight. A live prison recording in the late 1960s turned the same song into a chart-topper with crossover appeal. The six-figure settlement in the late 1960s became a footnote in music law as much as a chapter in Cash’s career.

Behind the facts are human tensions: a poverty-stricken songwriter hungry for a break; a small record label urging him to polish his act; a studio head who first dismissed the band as raw; and an obscure arranger whose nearly-forgotten torch song became the seed of a country classic. The ripple effects were felt beyond the music business — older listeners who remember hearing the record on radio or at live shows still recall how the train whistle in the song seemed to pull at a life they knew or feared.

The settlement did not erase the song’s reach. It sits now between two eras of Cash’s work: the lean Sun Records beginnings and the stadium-sized stature he later achieved. But the story stops at the moment when law and art collided — a sharp turn as sudden as any freight train.