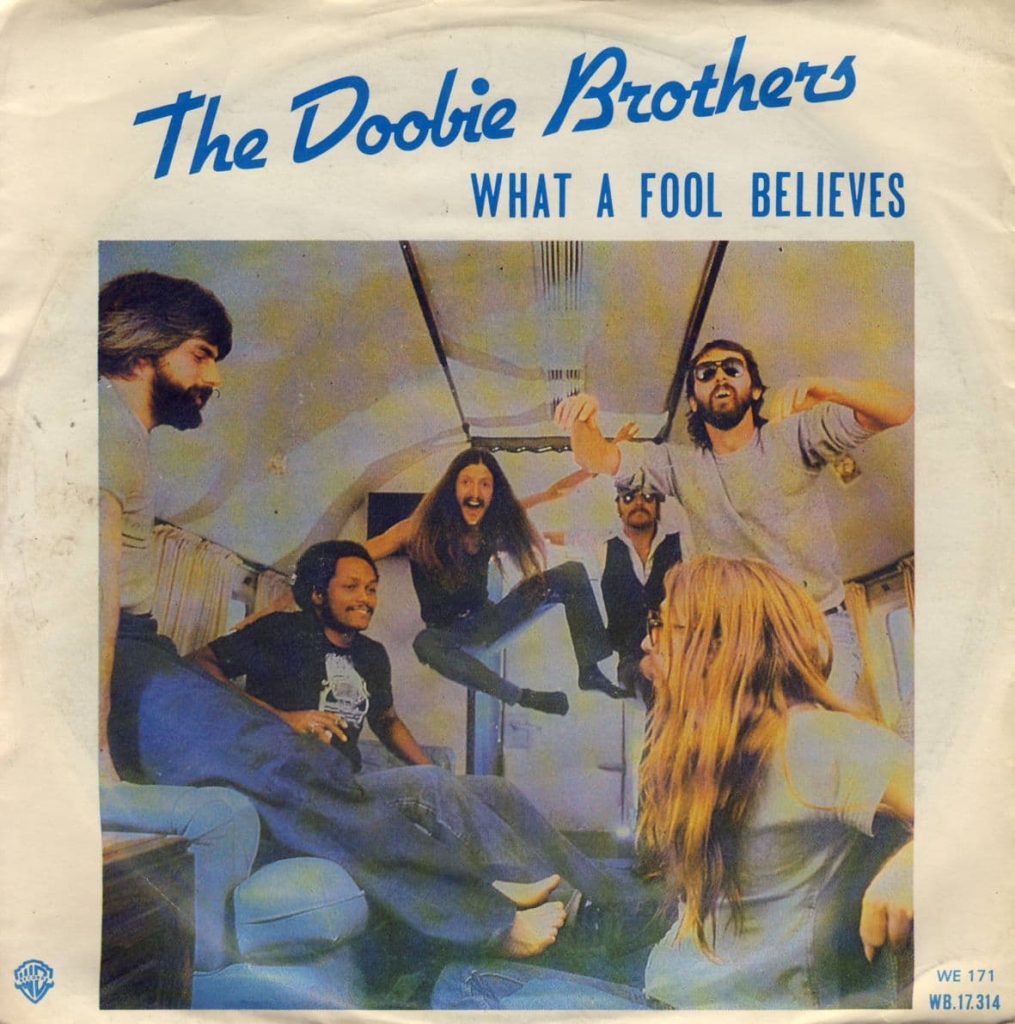

A single song lifted a band from bar-room favorites to a voice for a generation of quiet longing. “What a Fool Believes” arrived with a silkiness that still catches the breath — a small miracle of melody and memory that made the Doobie Brothers a household name.

Written by Michael McDonald and Kenny Loggins and released in the late 1970s, the track became the group’s most famous moment. It topped the charts and earned the band a major award for songwriting, yet the song’s power has never been only about trophies. It sits, gentle and sharp, on the border between memory and wishful thinking.

At its heart the song tells the story of a man who confuses what he hopes happened with what actually did. The words are spare and precise. Musically, the record is polished to a mirror shine: McDonald’s thin, pleading voice, a bouncing piano figure, warm synths and a steady rhythm section that keeps everything moving without rushing.

What a fool believes, he sees; no wise man has the power to reason away. — Michael McDonald, co-writer and lead vocalist

The recording was shaped in the studio by producer Ted Templeman and a group of musicians comfortable crossing pop, soul and light jazz. The result felt modern even as it leaned on classic songwriting craft. Fans heard more than a hit. They heard a small confession set to a perfect pop engine.

Musicianship is a quiet star on the track. The bass keeps a warm, rolling pulse while guitars add small, tasteful fills. The percussion is steady and unobtrusive. Then there is McDonald’s voice — fragile at times, full of reason at others — carrying the listener along the line between wish and truth.

Every instrument is precisely placed; the record breathes the way a live room breathes. — Ted Templeman, producer

The song’s chart success was swift, but its staying power is what matters to listeners now. Radio stations long after its first run kept it in rotation. New generations find it on streaming playlists alongside softer hits of the era. Older listeners remember hearing it at dances, on the car radio, in living rooms at parties. That longevity is no accident: the songwriting is small and clear enough to hold attention across decades.

The Doobie Brothers, a band that had been evolving for years, found in this song a new, soulful center. Michael McDonald’s arrival in the group shifted their sound toward smooth, layered arrangements and introspective lyrics. The move carried risks: some longtime fans missed earlier rockier textures. But the payoff was a broader audience and a song that helped define a musical mood for many.

Key facts stand out: the song was written by McDonald and Loggins, recorded for the band’s acclaimed album of that era, and awarded top honors by the music industry. Its mix of pop hooks, R&B warmth and studio precision made it both radio-friendly and artistically respected.

Behind the chart headlines were small moments that shaped the record: a piano riff rehearsed until it felt natural, vocal harmonies adjusted until they breathed in unison, a bass line quietly revised to make the whole thing glide. Those details made the difference between a pleasant tune and a classic.

The song’s narrative — hope tangled with delusion — touches a universal nerve. Listeners of a certain age remember loved ones, relationships and choices with a clarity that is part joy, part ache. That emotional mix is why the song still turns heads and opens conversations among friends who remember where they were when they first heard it, and among younger listeners who discover its calm, aching honesty.

And then, just as the record seems to settle into memory, the song’s final lines leave the listener suspended, wondering which of us is the fool and which of us has learned to see.