Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) arrived like a bright, insistent call from the hold of a ship — simple, rough, and impossible to ignore. What began as a Jamaican dockworkers’ chant became a worldwide hit that reshaped American pop and carried the voices of labor into living rooms across the globe.

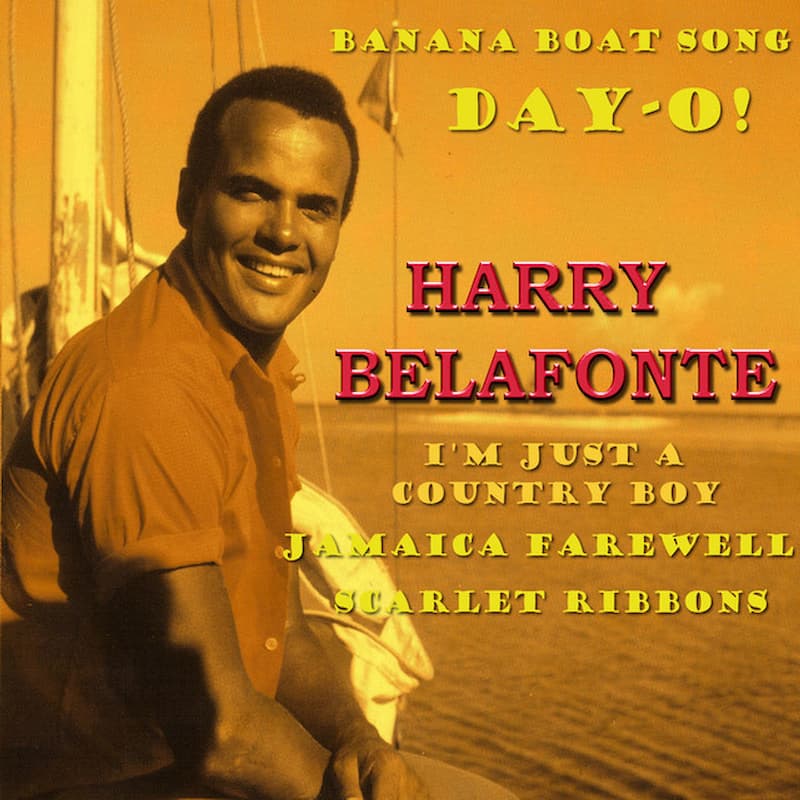

The song’s path from island work song to chart-topping single is a story of migration, memory and music. Harry Belafonte, born to Jamaican parents and raised in Harlem, learned the melody from his Caribbean roots and polished it on small stages in New York before recording it for RCA. The track opened his Calypso album and helped lift the record to unprecedented sales, while the single itself climbed high on pop charts and ran for many weeks — a rare achievement for a folk-derived number in that era.

Belafonte and collaborators William Attaway and Norman Luboff arranged the piece from a traditional mento work chant. Its call-and-response structure mirrors the real-life rhythm of night shifts loading bananas, a steady counting and yearning for daylight. Belafonte insisted on keeping that human texture rather than smoothing it into a glossy pop confection, recording with the Norman Luboff Choir, Tony Scott’s orchestra and guitarist Millard Thomas — a combination that kept the song earthy and dramatic.

The result was not merely a novelty. It sparked a calypso craze in the United States and opened many listeners’ ears to Caribbean traditions. Radio play and television spots turned “Day-O” into more than music; it became a cultural shorthand. It has been reused in films and ads, most famously in a darkly comic scene where the song underscored a supernatural possession, and later in documentaries that used the melody to underscore Jamaica’s economic struggles.

“I still hear my father singing it when he came home from the docks,” said Marjorie Clarke, 72, a longtime Brooklyn resident whose parents worked on Caribbean shipping. “It was the sound of sweat and counting and hope — everyone knew the lines.”

Music historians say the recording’s influence stretched beyond popular taste into the business of records. The album that held the song smashed sales expectations, selling in large numbers and helping make the LP a serious commercial format. Belafonte’s determination to keep the performance authentic reportedly caused friction with producers who wanted a softer, more mainstream version; his insistence ultimately helped preserve the song’s power.

“Belafonte’s insistence on authenticity changed how American audiences heard immigrant music,” said Dr. Alan Richards, a music historian at Columbia University. “He showed that a work song from a dock could be presented with dignity and still become a hit.”

The lyrics themselves are spare and haunting: repeated refrains of “Daylight come and me wan’ go home,” calls to a tally man to count bananas, and the stark imagery of lifting long bunches by hand. Those lines point to a world of long nights, low pay and close-knit labor rituals — a labor history condensed into a chant that becomes, in performance, almost celebratory. Mishearings and adaptations multiplied the song’s reach: cover versions by other artists in the same era found chart success overseas, and subsequent interpretations ranged from jazz-flavored takes to pop novelty spins.

Behind the cheerful rhythm is a complicated legacy. The song reminds older listeners of migration and work, and it has been pressed and repurposed in commercial settings that sometimes strip the context from its origins. Yet the core recording — Belafonte’s voice anchored by a choir and simple orchestration — keeps the human story audible: men tallying their loads, longing for daylight, and using song to get through the night.

Numbers matter in that story: the single rose to the upper ranks of the pop charts for many weeks, while the album that opened with it became one of the first LPs to reach a million sales within a short span, changing industry expectations and showing that American audiences would embrace music rooted in another country’s