Before becoming an iconic anthem symbolizing the turbulence of the late 1960s, “Fortunate Son” was unleashed as a sharp and urgent single by Creedence Clearwater Revival in October 1969. Initially released as the B-side to the lighter “Down on the Corner,” it quickly transcended its flip side status, soaring to No. 14 on U.S. charts by November 22, 1969. Following Billboard’s change in chart methodology, the double A/B single peaked dramatically at No. 3 on December 20, riding on its raw energy and unyielding message. Recorded at the famed Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, this brisk 2:18 track, penned and produced by the ferocious John Fogerty, went on to earn the prestigious RIAA Gold award by December 1970. Significantly, decades later, in 2013, the Library of Congress honored “Fortunate Son” by adding it to the National Recording Registry, while Rolling Stone magazine shuffled its ranking from No. 99 on past “500 Greatest Songs” lists to No. 227 in 2020, illustrating how the song’s profound cultural grip remains firmly intact despite changing canonical tastes.

“The anger behind ‘Fortunate Son’ wasn’t just about the war— it was about class,” said John Fogerty in a recent interview. “It was always about those getting sent to fight and those getting kept safe—the rich making war and the poor fighting it.”

The stark truth behind the song was in its very heartbeat, a scathing critique rather than a mere war-time lament. Amid the chaos of the Vietnam War, Fogerty’s rage was laser-focused on the class divide—the privileged who dodged danger versus the dispossessed who bore its brunt. Sparked by symbolic injustices like the lavish wedding of David Eisenhower and Julie Nixon, where powerful families’ sons appeared shielded from the draft, Fogerty’s lyric sting opens with the defiant cry, “It ain’t me,” marking not a betrayal of country but a refusal to accept a rigged system.

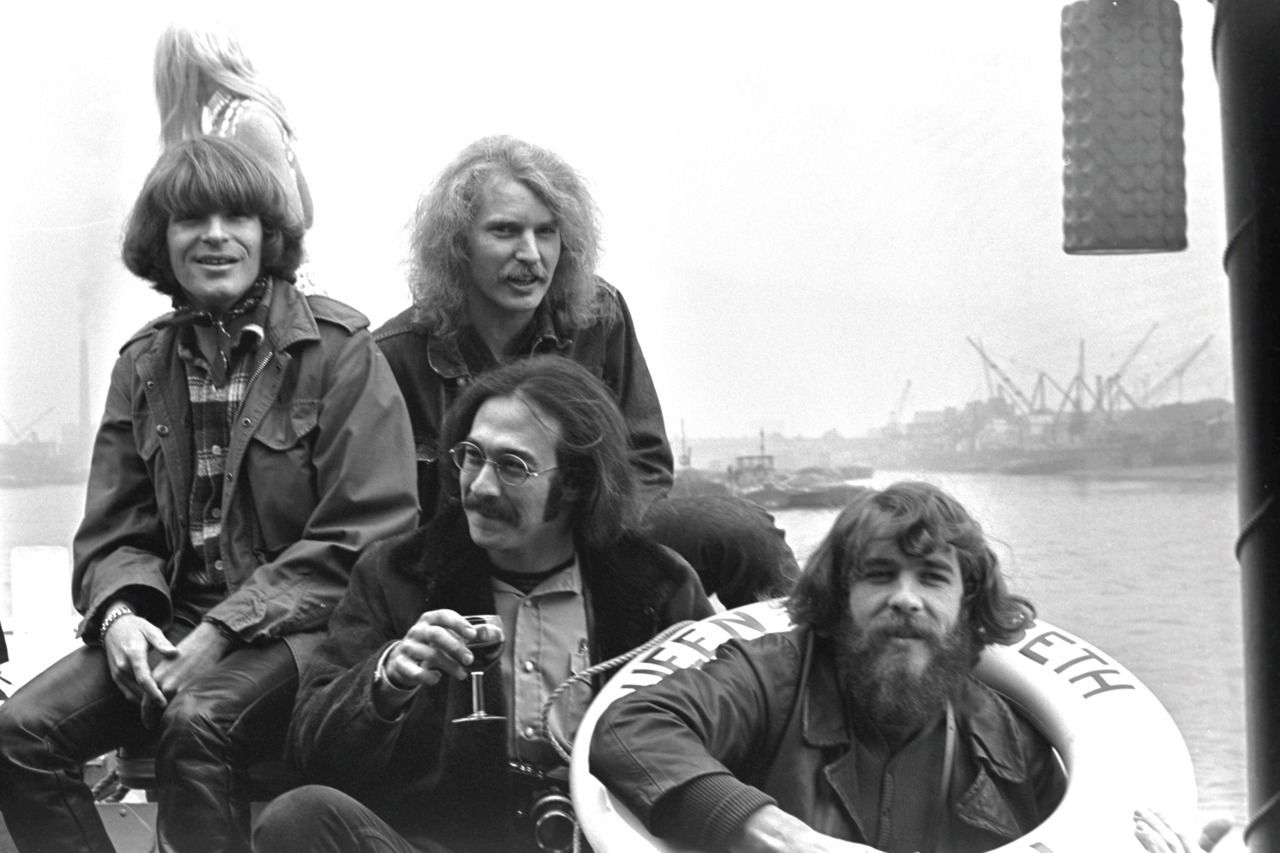

Musically, Creedence Clearwater Revival delivers their cleanest, most distilled sound in this track—no excess, no preaching. A sharp snare crack and a serrated guitar riff combine with Fogerty’s commanding vocals cutting through the mix like a siren. There’s no room for embellishments or extended solos; instead, the song’s tight and fast tempo drives relentless forward, embodying impatience with hypocrisy and deception. Its chorus pounds the indictment home—a complicated truth rendered instantly comprehensible in under two and a half minutes, making it a model of powerful succinctness.

“When you hear that riff, you feel it—not nostalgia, but recognition,” said longtime band associate David Niles. “It’s like a voice refusing to back down, telling you the truth about power and privilege.”

In 1969, as CCR released three albums, Willy and the Poor Boys emerged as a fiery statement, capturing the unsettled spirit of its day. While “Down on the Corner” smiled and invited foot tapping, “Fortunate Son” revealed its teeth, a raw articulation of class-based injustice. Billboard’s odd charting methods might confuse the timeline, but the impact was crystalline; millions identified with its potent combination of gritty guitar and compelling vocal. The Library of Congress aptly described it not as a song about war per se, but about deciding who pays the price before the all-volunteer military era.

The song’s persistence in films, TV, and cultural memory—often accompanying carousel scenes of helicopters over jungles—has granted it a second life. It became shorthand for the era’s disillusionment, quickly conveying the mood without words. Yet this ubiquity sometimes obscures the song’s broader critique: entrenched privilege shielding the powerful. Fogerty himself has expressed discomfort when “Fortunate Son” is appropriated for patriotic pageants at odds with its dissident message. Still, its lasting presence underscores how a brief, two-minute lightning bolt of sound can encapsulate a generation’s struggle against entrenched power.

Today, as older listeners revisit “Fortunate Son”, its sting morphs into clear-eyed clarity. The record stands as a reminder of an era when citizenship was conflated with blind obedience, when waving flags sought to silence probing questions. Yet it equally preserves the rebellious spirit—the gumption to say “I love my country enough to demand better”. That’s the knot Fogerty weaves—a fierce dissent layered within an unmistakably American groove. The drums beat the call, guitars churn with intensity, and the voice never flinches, indicting empty slogans and unveiling patriotism without fairness as a mere mask.

More than just facts or nostalgia, the magic of “Fortunate Son” lies in its power of recognition. It doesn’t just soundtrack a moment — it clarifies it with unwavering boldness. Listeners might recall what it felt like to realize loving a place means sometimes shouting dissent loudly, two minutes at a time. That raw, fearless voice breaking through is the song’s enduring gift and why, over half a century later, “Fortunate Son” remains a rebel’s battle cry echoing through time.