A terse, weary counsel about disappointment — “Take It Like a Friend” is a polite jab wrapped in resignation, asking that loss be borne with the dignity of a companion rather than the fury of a rival.

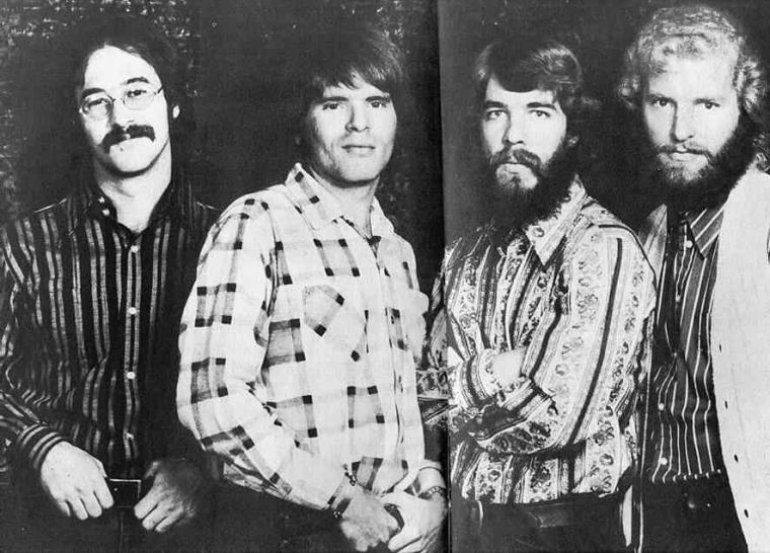

“Take It Like a Friend” appears as the second track on Creedence Clearwater Revival’s final studio album Mardi Gras, released April 11, 1972; the song was written, sung and credited to bassist Stu Cook as part of the record’s unusual impulse to distribute authorship among the remaining members.

At its most literal level the lyric is a domestic parable: someone who once assumed they had the moral claim to a situation finds themselves edged aside, and the narrator offers a curiously calm admonishment — “Hope you take it like a friend” — where spite might have been expected. Read against the album’s fraught backstory, the line becomes freighted. Mardi Gras was recorded after Tom Fogerty’s departure and during a period of open tension about creative control; the record’s cover of responsibilities — each member supplying originals and lead vocals — is widely interpreted as both an attempt at fairness and a document of fragmentation. That context makes “Take It Like a Friend” feel less like a private love-letter gone wrong and more like a note left on the kitchen table after an argument about who runs the house.

Musically the track carries Creedence’s familiar working-class vernacular: lean guitar lines, direct percussion, and a vocal delivered without artifice. Yet it lacks the single-minded propulsion of earlier Fogerty-penned hits; instead, Stu Cook’s voice and arrangement give the song a casual, conversational quality. There is an ordinary cadence to his phrasing — the kind of thing you hear from someone explaining, with small patience, that they will not be bullied out of their place. That ordinariness is part of the song’s power: it asks listeners to feel the injury not in cinematic melodrama but in the quiet, private tone of everyday disappointment.

For older listeners who came of age with Creedence’s late-60s and early-70s catalogue, returning to this track now is to witness the band’s internal life leaching into its art. Where John Fogerty’s earlier songs acted like proclamations — clear, mythic statements about boats, rivers, and hard luck — “Take It Like a Friend” reads like a domestic aftershock. The lyric’s small images (“gather up your chips,” “playing cards too close”) point to gamesmanship and social etiquette; the chorus’s restrained pity — “It was over ’fore it started… Hope you take it like a friend” — feels like the last, civil word of someone who has decided to walk away with their dignity intact rather than to answer in kind. The result is a moral smallness rather than grandeur, and for many listeners that ring of humility is more recognizable, more human, than heroics.

There is also an archival melancholy stitched into the performance. Mardi Gras climbed the charts more because of Creedence’s reputation than because the material suggested a bold new direction: the album reached respectable positions and later received scrutiny as an awkward final chapter in an otherwise remarkably consistent catalogue. Hearing Stu Cook step forward as songwriter and lead on “Take It Like a Friend” is to sense an attempt at democratic repair, an effort to rebalance authorship that arrived too late to heal the real rifts. That makes the song a kind of bittersweet artifact — not simply a B-side sentiment but evidence of a band trying to diffuse one final argument with melody.

What holds the track together for listeners who now bring more years and more losses to the listening experience is its tempered voice. The song does not rage; it reframes. It teaches the odd, adult lesson that sometimes the gracious thing is to recognize the end of a claim and to offer the parting as a favor rather than as a wound. That moral economy — the refusal of spectacle in favor of a small, courteous closure — is what gives “Take It Like a Friend” its unexpected tenderness. For those who remember a younger Creedence that sounded like thunder and for those who have followed the members into quieter retrospection, the song reads as both the echo of a disagreement and an invitation: accept the loss with a measure of friendship, and live to tell about it.